This was first published on 18 March 2014. It does make reference to a previous posts on my old blog (I’m reposting these in backwards) such as Les Filotas’ Improbable Cause and the 1946 Stephenville AOA disaster. I will post those ones as well, even if Filotas’ work is a controversial publication (I have a rule with one colleague that we not discuss that crash until he visits the crash site. Otherwise we will agree to disagree on many points), and will update the links as the blogs are reposted. As I said, this is a great reference book, a great starting point for research, but some information within the book does need verification.

I would also like to apologize for a number of book reviews in a row, but I am working on more incident reports and thesis edits of crash sites to be published. At the same time, I am always trying to read more and do more research, which means book reviews. I am also working on a couple of posts looking at methods to be used in aviation archaeology; methods which anyone with just a few inexpensive pieces of equipment can do.

Disaster in the Air by Colonel Edgar A. Haine (published in 2000 by Cornwall Books, New York) was recommended to me by a descendant of the navigator who perished in the 1946 Stephenville air disaster. It also came with the warning that some facts and figures should be checked, as her grandfather’s name was misspelled.

According to the dust jacket “This book is mainly concerned with the serious subject of airplane safety” and details “eighty-nine of the world’s most serious (in terms of human lives lost) airplane disasters starting in 1927”. As the focus of this blog is Newfoundland aviation, I will only look at the disasters listed for this area, but the text does make for a good reference point if researching any air disaster, particularly if an American aircraft is involved. Many well-know crashes are profiled, such as PAN AM Flight 103 which crashed over Lockerbie, Scotland and TWA Flight 800 east of New York, but others, such as the 1946 Sabena crash in Gander, Newfoundland and the 1998 Swissair Flight 111 disaster off the coast of Nova Scotia are not covered, both with heavy casualty rates for the time. An updated edition would be nice to include Air France Flight 4590, the aircraft involved in 9/11 and others to maintain its status as a good reference book. The introduction is well written and explains why aircraft disasters and incidents need to be investigated, and the steps of an investigation and how they have changed with the types of aircraft, technology and with the advent of devices like the black box. The introduction then goes through the evolution of safety boards and regulations, with an American focus, and how those changes were reflected by, or caused by, the number of disasters in different time periods. Again, such an overview is a great starting point for any research, and explains it in a clear manner that anyone can read.

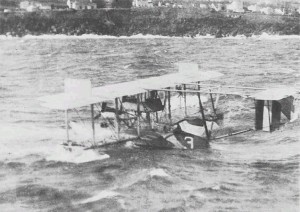

Prior to delving into the disasters, Haine give a brief overview of early aviation history, again, with a focus on American aviation history. He starts with the Wright Brothers, into the Daily Mail prize, the successful flight of the Curtiss seaplanes from Newfoundland to Lisbon in 1919 (with a stop in the Azores as pictures above), to Alcock and Brown’s non-stop flight from Newfoundland to Clifden, Ireland through many other aviation firsts up to the end of the 1920s. Again, it is a wonderful overview of early aviation, and a good starting point for any research. Haine actually returns at the end of the books (Appendix 5: Biographical Information and Airplane Data) to discuss the specification of some of these early aircraft as well as those featured in the main part of the book (the disasters). Strangely, the major aviation accidents from 1927-1998 are listed in a table in chronological order, but the individual accident narratives are actually in reverse order, starting with 1998. This is a little odd as the reason for including many of the incidents are that they are the worst disaster of that time, but the impact of this is lost when looking at the incidents in reverse order. As well, listing them in chronological order would have better showed the evolution of the aircraft and safety standards, something touched on in the introduction.

Site of the Arrow Air Crash in Gander, Newfoundland, overlooking Gander Lake. Photo by author, 2008.

Only two Newfoundland incidents are listed in this text, “12 December [1985]. Arrow Air Crash, Gander Newfoundland, 256 deaths” and “3 October [1946]. DC-4 Crashes in Newfoundland, Killing 30 Persons.” The Arrow Air Crash is covered in under a page, looking at the route, the crash and the investigation. According to Haine, sabotage was quickly ruled out and the cause, though undetermined, may have been due to the aircraft being overweight and/or no de-icing although there was freezing rain falling prior to takeoff. It is a simplistic look at the crash, but, as this book is an overview, it is a good place to start. For something more detailed, try Improbable Cause by Les Filotas.

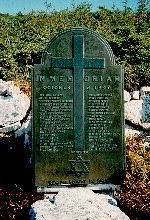

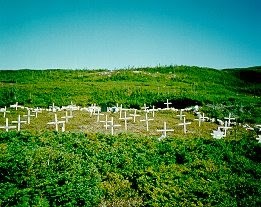

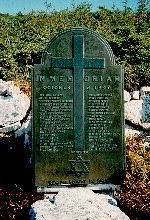

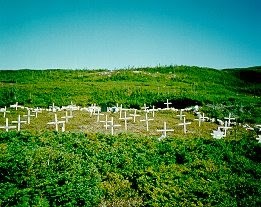

The 1946 Stephenville DC-4 Crash is much more detailed. Haine discuses the planned route for the aircraft, how it was diverted to Stephenville due to Gander being “socked” in and early theories regarding the crash. Over four pages, the author discusses the rescue/recovery parties that went to the site, the investigators who visited the crash the day after the crash and the efforts made to comply with family wishes for funeral arrangements and the final outcome of the site. Back in the introduction of the book, it is stated that “in one case, in Newfoundland in 1946, the wreckage and intact bodies were simply covered over by an avalanche of rocks, generated by a powerful explosion, in order to obliterate all traces of the calamity.” This indicates that it is the only time this has been done. While other research has shown that the remains were in fact collected, put in a mass grave, then the site covered by blasted rocks on 5 October 1946. Haine also states that “an acre plot of ground, surrounding the jutting cliff, scene of the crash within sight of Harmon Field, was set aside as an official cemetery”. It is assumed that this includes the memorial cemetery above the crash site.

Images of the memorial cemetery from heritage.nf.ca. Note, since this image was taken, many of the wooden crosses have fallen.

The article ends with a discussion of the investigation and the findings by the Board of Inquiry. The Civil Aeronautics Board determined the probable cause of the investigation as “the action of the pilot in maintaining the direction of takeoff toward higher terrain over which adequate clearance could not be gained”. The author indicates that this disaster, as one of the largest at the time with high civilian casualties, would have to prepare the public for increasingly larger disasters due to the “rapidly increasing size of air transports”. Overall, the book is an excellent reference tool, and good as a starting point for the investigation of any incident. The fall-backs are that it is not as comprehensive as it would lead a reader to believe in the introduction, and facts are not cited nearly enough. While many end-notes can be used to find more sources, many accidents are not references at all (i.e. the Arrow Air crash in Gander). If you have an interest in aviation history, this is worth having in your collection, just be sure to verify its information.